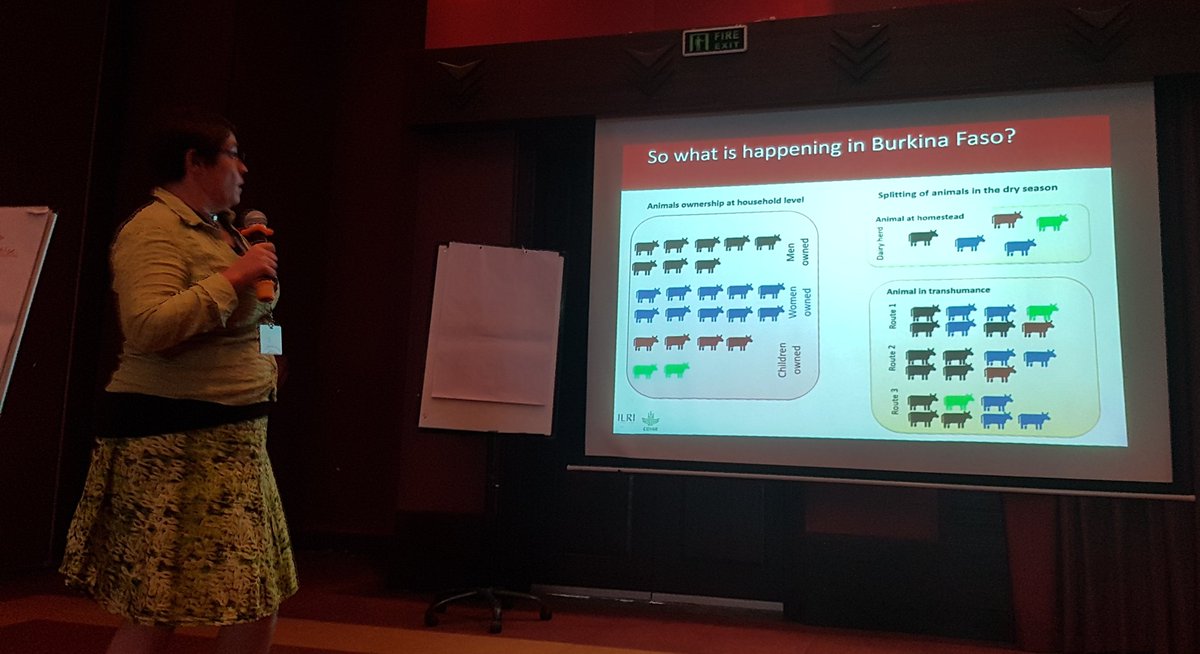

It has been a very busy end of the year, and i am just noticing that my blog remained silent for two moths and many of the interesting learning will only appear in 2018. But as the end of the the year approaches, it is time to reflect about 2017 first. It was a year that took me to Burkina Faso and Ethiopia twice for the CLEANED project that aims to assess environmental trade-off of intensifying livestock value chains in developing countries, to Somaliland where i have been setting up a GIS lab and working with the local government on the livestock sector, and to Northern Kenya.

So what did 2017 bring? for me it was the year where I engaged with pastoralists across Africa, in Burkina Faso, Somaliland and Kenya and discovered a fascinating world, where all the logic I know about was challenged.

Pastoralists have a very different way to see the world than the smallholders farmers I usually work with. And it might sound stupid, but because pastoralists are moving with their animals in very harsh environment, they are not really interested in accumulating "stuff" that is heavy to carry around and they are used to live with almost nothing. This is why many of the incentives that we usually use, such as money or in kind just do not work.

Pastoralists value their community and their animals. Therefore, working on the relationship with these communities and build up trust is the better incentive than some materialist item. Also, I have discovered that pastoralists have their own information sharing mechanism that they have developed and improved over centuries and nobody is waiting for any phone app to bring a revolution, they have the information they need. Also information is shared within relevant networks within clans, and there are good reasons why that information is not public : governments do not know how many pastoralists are crossing boarders (a concept that is nonexistent to many pastoralists) and therefore cannot tax animals going from one country to the next, others clans who might compete on ressource might not yet know where the good pastures are. So bringing digital products to this world might do more harm than good, and a better understanding of what information can be shared with whom is necessary before thinking of digital products.

Across all countries, pastoralism is under pressure. There is often conflict on land among pastoralist clans themselves, as in many places the number of livestock is above the carrying capacity of the land which has led to serious land degradation and a resulting lack of available feed and fodder. Also there are conflicts between pastoralist and crop farmers, on who has the right to use the land. Pastoralism is often seen as an old-fashioned lifestyle that is doomed. But especially, in Western Africa there is a strong movement to fight for the right for such a traditional lifestyle.

Meeting pastoralists and working with anthropologists this year have changed the way i look at agricultural intensification in Sub-Saharan Africa. Clearly, there is an urgent need to increase food production in Africa where population will double over the next 30 years. High potential area, where rain is abundant and soils are fertile, will have to play a big role in producing more food, also smallholder farmers in those area are keen intensifying there production that they believe will bring more income. But, in dry low potential areas it is less clear what intensification of production can bring, and people making use of these area have a right to choose their lifestyle, even if it goes against the mainstream thinking. Who are we to push pastoralists towards something they do not believe in for the sake of feeding the world?

Clearly, in the transition zone, between the high potential area and dry rangeland, conflict between the two world emerges. In those zones, land use planning and clear rules that regulate fair access to land and its biomass need to be implemented so that both pastoralists and non-pastoralist can co-habitate. Combined with efforts of land rehabilitation, and emerging opportunities outside of the agricultural sector that can offer jobs to those who do not want to remain a pastoralist, might support a productive and sustainable traditional pastoral production that sustains a decent livelihood for those who choose to live in this way.

As we move to 2018, let's keep an open mind to those who go through life differently and learn to appreciate what they can teach us, the same way pastoralists have reshaped my understanding of agricultural intensification this year. I remain with thanking you for following this blog, that in the meanwhile has up to 2500 clicks a month, and wish you a happy new year!

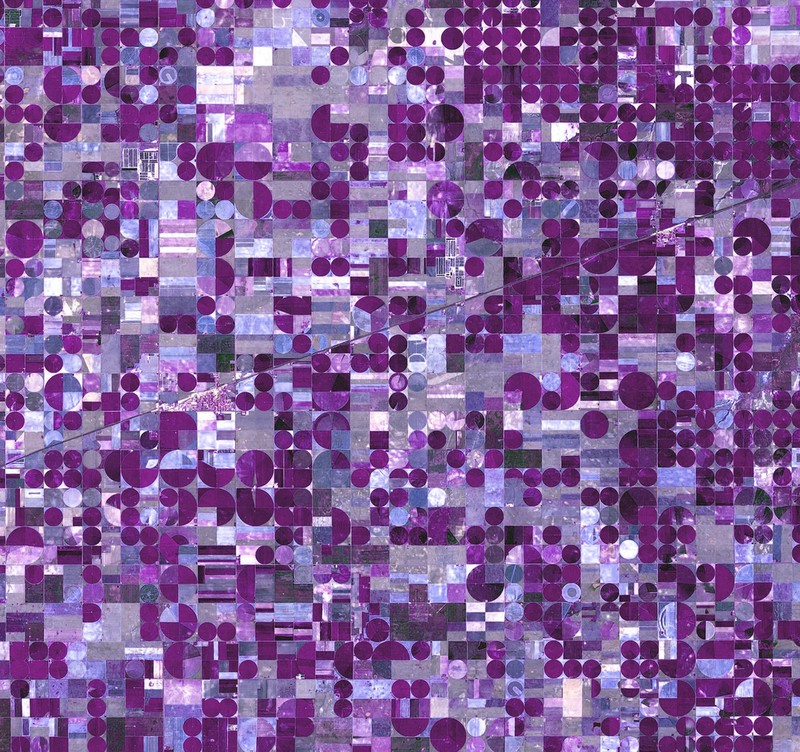

Note that all pictures in this post are taken from

here. They are made

Gille Coulon, an award winning photographer. He has exhibited these pictures at the "centre culturel francais" in Ouagadougou, an exhibition that was lucky to see during one of my many visits in Burkina Faso.